Bruce Pelletier was born and raised on Chicago’s Northwest side in the Old Irving Park neighborhood. His Chicago roots are noticeable not only because of his accent. He also has that outgoing, Midwestern charm that you would expect from any life-long resident of the city.

Bruce has had his share of obstacles and challenges in life, but one of the biggest struggles he faces is his battle for stable mental health. On top of this, Bruce also experienced housing instability on and off for years, making it nearly impossible to fully focus on bettering his mental state. He now resides in Uptown, a Northside Chicago neighborhood, where he has lived for just over a year due to the support he received from the Better Health through Housing (BHH) program. BHH is a housing-first program coordinated by the AIDS Foundation of Chicago’s subsidiary organization, the Center for Housing and Health. The program focuses on connecting people directly to stable housing and supportive services in order to improve participants’ health outcomes.

However, before BHH came into his life, Bruce came up with a creative solution to ward off homelessness – he became a truck driver.

“That’s why I got into trucking. I was homeless then and I thought I would eliminate that problem by driving … I would always have a place to sleep,” said Bruce.

He remained a truck driver for 20 years and loved the freedom that came with being on the road. The long days and nights kept Bruce on the go and gave him a steady income to support himself and meet some of his basic needs. He was even able to pursue his passion for journalism by writing for websites like CDLlife.com, where he could write about all things trucking. However, his solution abruptly came to an end in 2013 when Bruce lost his license after receiving a DUI. Thankfully, he was able to stay at his girlfriend’s place at the time while he figured out his next steps. For years, Bruce looked for new work and handled all his court dates from his DUI case all while managing to take classes at a community college to further pursue his career in journalism.

“I didn’t have a car, so I would bike or walk everywhere,” said Bruce. “I had to walk to court, then I had to walk to school. My feet were always on fire … I couldn’t let transportation be a factor for me. If I can walk, I’m going to get there.”

Things for Bruce were stable until one day in 2017 when Bruce and his girlfriend’s son got into an argument that resulted in Bruce being kicked out of the house. This ultimately ended his relationship with his girlfriend and, again, Bruce was out on his own.

“Because her son used violence on me and I protected myself, they were not having it. So, I said, ‘I’ll just leave,’” Bruce recalled. “We made an agreement and I left out of there and I went to my sister’s house. Then, they started with their shit and I said, ‘No I’m trying to finish school. You all are not sabotaging this,’ so I left.”

Bruce was out of places to stay, so he resorted to different shelters throughout the city. However, because of the high traffic, strict curfews and lack of privacy that comes along with staying at a typical shelter, it was challenging for Bruce to keep up with school. Bruce figured he would be better off living on the street for a while.

“I got me a tent and I pitched it over there by the lake,” said Bruce. “Luckily, I had a good therapist over there at Wright College because I was about to lose it. It was April, so it was raining a lot and I just … I was getting these dark thoughts and I kept thinking, ‘No man, you can’t do this. You’re almost done graduating.’ Lo and behold, I talked to my therapist at Wright College and she had told me about Swedish Covenant.”

Swedish Covenant Hospital is located on Chicago’s Northwest side, not too far from where Bruce is originally from. He visited the hospital up to twice a month while he was experiencing chronic homelessness to address his suicidal thoughts and have a warm place to sleep when he was admitted into their psychiatric ward.

“I didn’t have a place to stay and I was in a really bad place [mentally]. I just wanted to die … I had all of these suicidal thoughts all the time,” said Bruce.

After two months of living on the street, things started to look up for Bruce. He finally heard back from an interim living program that he had applied to and learned that he was accepted.

“Every Sunday, I would check in to see what my status was. Then, one Sunday they said ‘You’ve been selected. Congratulations, come on, Bruce!’ … it was like getting into heaven,” he said. “It was such a blessing and it couldn’t have happened at a better time because right when I got in, I had signed up for a summer class and I just thought ‘Oh great! I have a bed to sleep in now, I got a hot shower, warm meal, cold breakfast. Life is good.’”

Because he was in school, Bruce had special permission to leave the shelter early in the morning to make it to his classes and maintain his enrollment. However, even with those special permissions, Bruce was written up several times for missing curfew.

“I wanted to get up out of there because I didn’t want to be in the shelter, I wanted to be on my campus. That was my support system. [The shelter] was just there for me to sleep,” said Bruce. “I love Wright College. It’s such a great community … They saved my life. They helped me break out of that arrested development of that fear and loathing. It’s good knowing that I can pursue my dreams.”

By the time Bruce was on his third strike for missing curfew, he received even better news and a call that changed his life forever.

“A case manager was getting ready to make me sign a contract because I had missed curfew again. They were getting ready to throw me out of there,” said Bruce. “Lo and behold, I got a call and someone said ‘Bruce, come on in. We got an SRO [single room occupancy] for you.’ The timing could not have been better.”

Little did Bruce know, his regular visits to the Swedish Covenant Hospital’s emergency department flagged him as a patient who was both experiencing chronic homelessness and living with a chronic health condition. Swedish Covenant Hospital was one of a handful of hospitals in the Chicago area that was part of the innovative BHH program, which provides supportive housing for Chicago’s most vulnerable individuals.

Bruce wrapped up his stay at the interim shelter by graduating from their program and then moved straight into the SRO in Fall of 2017.

“When I got the SRO, I just thought, ‘Yay! Now I’ve got my own place to study!,’” said Bruce. “I loved it and hated it at the same time. At least it was better than living in the tent.”

During Bruce’s stay in the SRO, he worked with his case manager to find a more permanent housing solution. This venture lasted for 2 months until he finally landed his current apartment.

“I love my place now. It’s so beautiful,” said Bruce. “It was such a blessing. I pray to God every day in the morning and say, ‘Thank you Lord for this house, thank you for this food, thank you for all the blessings.’ I consider it a miracle, not even a blessing because I’m not in the street no more. I’m not sleeping in a tent, in a friend’s car or sleeping on the train.”

Despite everything he has been through, Bruce still tries to keep a positive outlook on life.

“I’ve made a lot of mistakes,” said Bruce. “I fall on my face and know how to get back up, but when I get back up it’s kind of a roller coaster ride. With the support systems and the communities that I’m involved in now, I’m staying more focused now with the task at hand and what my prime directives are.”

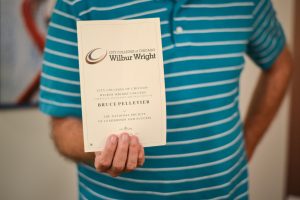

One of Bruce’s favorite sayings is “Nothing is permanent,” which got him through some of his darkest times. Now, things are looking better than ever. Bruce just re-signed the lease to his apartment for another year and is wrapping up his studies at Wright College. He has plans to continue pursuing his passion for journalism and hopes to be a full-time journalist in the near future.